100 years on from a remarkable revolution of visionaries and poets, 1916 - Visionaries and Their Words explores the writings and ideals of the leaders of the Easter Rising, in a concert programme inspired by their lives, their work, and their words.

100 years on from a remarkable revolution of visionaries and poets, 1916 - Visionaries and Their Words explores the writings and ideals of the leaders of the Easter Rising, in a concert programme inspired by their lives, their work, and their words.

With new music drawn from writings of the rising's leaders, as well as existing songs in the tradition from their pens, sean-nós composer, Lorcán Mac Mathúna will attempt to interpret the vision of these revolutionaries and to explore their legacy and ideals.

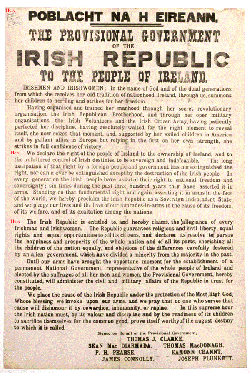

Inspired by the words and spirit of the proclamation, 1916 – Visionaries and Their Words, presents an audiovisual experience of music, song, and archive imagery and an artistic response to the words and vision of The Risings leaders. This concert will feature male, female, and children's voices to celebrate the part played by the people of Ireland in this most momentous event in Irish history in the 20th Century.

Since its release in October 2016 Visionaries 1916 has steadily garnered praise from all sources. The UK's most respected Folk and World Music publication fROOTS called it "Startingly origional" and said "Voices and fiddles rise and soar skywards in Joseph Plunkett's The Cloud."

Other words of praise include: (The Cloud) "Majestic, mournful soaring" FATEA; "'Daybreak' bursts into your senses and refuses to be contained" FOLKPHENOMENA "this album has wowed me from the beginning" FOLKROCK.DE

;

Visionaries 1916, which was released on October 15th in the Pearse Museum, St. Enda's, honours the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising through a creative musical use of their words.

Featuring the music of the show, 1916 - Visionaries and Their Words, it contains songs of Pearse, Plunkett, and Connolly, and traditional music reflective of Ceannt's love of the Uilleann Pipes and Fiddle.

Joseph Plunkett's technical mastery of poetic meter and of clarity of language lends beautifully to music. That is why we featured four of his songs in the show 1916 - Visionaries and their Words. Daybreak is one of his sonnets and it has a clear iambic meter running from start to finish. The melody we put to it makes use of this rhythm counterpoint to the full. Listen and enjoy!

“naked I saw you,

o beauty of beauties”

These are the opening lines of Padraig Pearse’s transformative poem “Fornocht do Chonac thú.” Pearse had taken a trope of modern Irish poetry and transformed it into a powerfully symbolic gesture of self-sacrifice and heroism.

These are the opening lines of Padraig Pearse’s transformative poem “Fornocht do Chonac thú.” Pearse had taken a trope of modern Irish poetry and transformed it into a powerfully symbolic gesture of self-sacrifice and heroism.

In doing so, he not only provided an answer to a burning question in the revivalist Gaelic literature movement -whether the nascent modern Irish literature should reference ancient Gaelic literature or should be derived from the folk vernacular- but he inverted the Aisling and tied the imagery of nationalism to the sacred ideal of self-sacrifice.

During the era of the penal code in Ireland the political Aisling became an ubiquitous statement of Gaelic nationalist aspiration. In the Aisling, the poet is visited by a vision; a supernatural embodiment of the sacred ties of homeland, and incited to take on his duty and expel the foreign oppressor. The Aisling promises that the reward of duty will be liberty.

There are so many examples of these poems, preaching the same message; revolt and you will be liberated.

Pearse describes a different type of vision. In fact his poem centres around knowing that the price of duty is death. It is a toll that he struggles with and turns from; before finally accepting his duty and his destiny.

In Pearse’s Aisling, duty is a burden which will extoll the highest price. He joins the nationalistic fervour of this most politicised poem to the religious symbolism of Christ’s passion. Like Christ, he knows that his duty will lead to death and he fears accepting it. Like Christ, he agonises over whether he should chose duty or life, and like Christ he accepts duty and its consequent price.

Pearse’s symbolism is so powerful, and is heightened by a syntactical ambiguity which he opens with, but doesn’t quite answer. “Naked I saw you”

Who is naked? Is it the poet, bereft of uncertainty; of chance; vulnerable and helpless before the enormity of his destiny? Or is it the Vision which is naked, revealing all with dreadful clarity?

In the Aisling tradition, Duty rewards with liberty. In Pearse’s Aisling, Duty promises death. But it also promises a thing which Pearse preached increasingly, a noble sacrifice that can transform a nation.

A prominent Dublin employer, Jacobs (which was occupied during the Easter Rising by the Irish Volunteer 2nd battalion under the command of Tomás Mac Donnagh) had been a player in tensions between organised labour and the business elite, of the decade before the Rising.

A prominent Dublin employer, Jacobs (which was occupied during the Easter Rising by the Irish Volunteer 2nd battalion under the command of Tomás Mac Donnagh) had been a player in tensions between organised labour and the business elite, of the decade before the Rising.

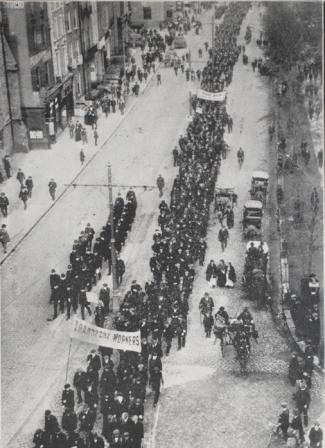

They were one of the employers who dismissed union members in the Lockout of 1913, and in 1911 the factory came to a standstill when 3,000 of its female employees – including a young Rosie Hackett – embarked on a sympathy strike in support of the men.

The sympathetic strike was a controversial weapon employed by the unions. Harking back to the tactic of boycott from the Land War –which Connolly would have witnessed himself while stationed in Ireland as a private in the British Army- it was an escalation of industrial dispute which illustrated Connolly’s belief that the conditions of individual workers was symptomatic of a wider issue of class conflict.

At the height of the lockout in 1913 Connolly wrote an article for Joseph Plunkett’s publication, The Irish Review, explaining the thinking of ‘the sympathetic strike’. Here is an extract of his article.

“What is the sympathetic strike? It is the recognition by the working class that their essential unity, the manifestation in our daily industrial relations that our brother’s fight is our fight, our sister’s troubles are our troubles, that we are all members of one another.

“What is the sympathetic strike? It is the recognition by the working class that their essential unity, the manifestation in our daily industrial relations that our brother’s fight is our fight, our sister’s troubles are our troubles, that we are all members of one another.

The union is evolving among its members a higher concept of mutual life, a realisation of their duties to each other and to community at large, and are thus building for the future in a way that ought to gladden the hearts of all lovers of the race. In contrast to the narrow, restricted outlook of capitalist class, and even of certain old-fashioned trade-unionism, with their perpetual insistence upon “rights”, this union insists, almost fiercely, that there are no rights without duties, and the first duty is to help one another.

For the immediate present, the way out of this deadlock is for all sides to consent to the formation of a conciliation board, before which all disputes must be brought. Let the employers insist upon levelling up the conditions of employment to one high standard; treat as an Ishmael any employer who refuses to conform and leave him unassisted to fight his battles with the union; let the union proceed to organise all workers possible, place all disputes as to wages before the Board for discussion, and only resort to strike when agreement cannot be reached by the board; and all employers would be interested in bringing the more obdurate and greedy to reason, strikes would be rare.

For the immediate present, the way out of this deadlock is for all sides to consent to the formation of a conciliation board, before which all disputes must be brought. Let the employers insist upon levelling up the conditions of employment to one high standard; treat as an Ishmael any employer who refuses to conform and leave him unassisted to fight his battles with the union; let the union proceed to organise all workers possible, place all disputes as to wages before the Board for discussion, and only resort to strike when agreement cannot be reached by the board; and all employers would be interested in bringing the more obdurate and greedy to reason, strikes would be rare.

Thus we will develop a social conscience, and lay the foundation for an orderly transformation of society in the future into a more perfect and juster social order.”

During Easter Week, Jacobs factory, once seized by the rebels, saw very little conflict as the English forces bypassed it in preference for more strategic targets. In an interesting postscript to the story of Jacob’s, Thomas W. Bewley, secretary at Jacob’s, later wrote to Fr Aloysius Travers of the Order of Capuchin Friars Minor. His letter was accompanied by a cheque for £25 from the directors of Jacob’s to the Capuchins as a mark of appreciation ‘for the deep sense of thankfulness that our Factory was spared from serious injury during the time of the recent rebellion’.

During Easter Week, Jacobs factory, once seized by the rebels, saw very little conflict as the English forces bypassed it in preference for more strategic targets. In an interesting postscript to the story of Jacob’s, Thomas W. Bewley, secretary at Jacob’s, later wrote to Fr Aloysius Travers of the Order of Capuchin Friars Minor. His letter was accompanied by a cheque for £25 from the directors of Jacob’s to the Capuchins as a mark of appreciation ‘for the deep sense of thankfulness that our Factory was spared from serious injury during the time of the recent rebellion’.

Fr Aloysius returned the cheque, claiming that ‘any services that I may have rendered during the recent sad crisis were such as any other priest in the same circumstances would render’. He requested that the cheque be sent to the Lord Mayor’s Fund for the Relief of Distress.

As this was my first visit to Dublin, madam thought I might want to see some of the sights. She took me to a museum and suggested that we go to an Art Gallery.

“What I really want to see” I told her “is the poorest part of Dublin, the very poorest part”.

I do not believe there is a worse street in the word than Ash Street. It lies in a hollow where sewage runs and refuse falls; it is not paved and is full of holes. One might think it had been under shell-fire.

I do not believe there is a worse street in the word than Ash Street. It lies in a hollow where sewage runs and refuse falls; it is not paved and is full of holes. One might think it had been under shell-fire.

Some of the houses have fallen down, -from sheer weariness it seems, -while others are shored up at the sides with beams. The fallen houses look like corpses, the others like cripples leaning on crutches.

Dublin is full of such streets, lanes, and courts where houses, years ago condemned by the authorities, are still tenanted. These houses are symbolic of the downfall of Ireland. They were built by rich Irishmen for their homes. Today they are tenements for the poorest Irish people, but they have not been remodelled for the purpose, and that is one reason why they seem so appalling – the poor among the ruins of grandeur.

In one room, perhaps a drawing room, you will find four families, each in its own corner, with sometimes not as much as the tattered curtains for partitions. Above them may be a ceiling of wonderfully modelled and painted figures, a form of decoration, the art of which has been lost. At the end of this room is a mantel of purest white marble over an enormous fireplace long ago blocked up, except for a small opening in which a few coals at a time may be burned. The doors of such a room are often made of solid mahogany fifteen feet in height.

The gas company of Dublin refuses to furnish gas above the second floor, and the little fireplaces can never give enough heat, even when fuel is comparatively plentiful. As I write, coal is fifteen dollars a ton, and is costing the poor, who buy in small quantities, from thirty to forty five per cent more.

In Dublin there are more than twenty thousand such rooms in which one or more families are living. That epidemics are not more deadly speaks well for the fundamental health of those who live in them, for there are no sanitary arrangements. Water is drawn from a single tap somewhere in the backyard. The toilet, to be used by all the people in any one of these houses, is also in the backyard, or worse still, in a dark unventilated basement.

In Dublin there are more than twenty thousand such rooms in which one or more families are living. That epidemics are not more deadly speaks well for the fundamental health of those who live in them, for there are no sanitary arrangements. Water is drawn from a single tap somewhere in the backyard. The toilet, to be used by all the people in any one of these houses, is also in the backyard, or worse still, in a dark unventilated basement.

The head of the family in these one-time “mansions,” which number several thousand seldom makes more than four or five dollars a week! Of this amount, if they want the luxury of even a small room to themselves, they must pay about a dollar. Is it any wonder that the word “rent” has a fearful sound to the Irish? After this rent is paid, there is not much left for food and clothes. Starvation, even in time of peace, is always hovering near. Bread and tea for breakfast, but rarely butter; bread and tea, and either herrings or potatoes, sometimes with cabbage, for the mid-day meal; bread and tea for supper. Two fifths of the inhabitants of Dublin live on this fare the year round. If they have beef or mutton once a week they must eat it fried, since the fireplaces are too primitive for roasting or baking of bread or cakes.

The head of the family in these one-time “mansions,” which number several thousand seldom makes more than four or five dollars a week! Of this amount, if they want the luxury of even a small room to themselves, they must pay about a dollar. Is it any wonder that the word “rent” has a fearful sound to the Irish? After this rent is paid, there is not much left for food and clothes. Starvation, even in time of peace, is always hovering near. Bread and tea for breakfast, but rarely butter; bread and tea, and either herrings or potatoes, sometimes with cabbage, for the mid-day meal; bread and tea for supper. Two fifths of the inhabitants of Dublin live on this fare the year round. If they have beef or mutton once a week they must eat it fried, since the fireplaces are too primitive for roasting or baking of bread or cakes.

Yet Ireland could raise fruit and vegetables and grain for twenty million people! I have seen ships deep laden with food for need of which the Irish are slowly starving –I contend undernourished is starvation- going in a steady stream to England. The reason was that the English were able to pay better prices than the man at home. Food, since the beginning of the war, has literally been draining out of the country. Ireland today is in a state of famishment if not famine.

Here in Dublin, though the streets and lanes seem full of children, the death-rate is tremendously high. The population of all Ireland has decreased fifty percent in fifty years. In Poland under the rule of the Russina czar, the population increased. It is one thing to read about Irish “grievances,” it is another to be living where they go on year after year.

“Grievance” –that is the way the British sum up our sense of wrong, and with such effect that people the world over fancy our wrongs are not wrongs but imagined grievances. The word itself counts against us in the eyes of those who have never been to Ireland and seen foe themselves the conditions under which the majority of the population must live. To be sure, there are always complaints carried to Parliament and then a “commission of enquiry,” followed a little later by a “report upon conditions.” But the actual results seem small.

“Grievance” –that is the way the British sum up our sense of wrong, and with such effect that people the world over fancy our wrongs are not wrongs but imagined grievances. The word itself counts against us in the eyes of those who have never been to Ireland and seen foe themselves the conditions under which the majority of the population must live. To be sure, there are always complaints carried to Parliament and then a “commission of enquiry,” followed a little later by a “report upon conditions.” But the actual results seem small.

20/01/17 Wexford Arts Centre

31/03/17, 8pm An Táin Arts Centre, Dundalk

02/04/17 5pm Seán O Casey Theatre, East Wall, Dublin

29/04/17 8pm Culturlann, Belfast

24/07/17 Folk Holidays Czech Rep

30/07/17 Skibereen Arts Festival

30/01/16 Dublin TBtradfest

31/01/16 Dublin TBtradfest

02/02/16 Derry DITMF

11/08/16 Lorient France

Festival Interceltique

16/08/16 Ennis

Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann

30/09/16 Monoghan

Iontas Arts Centre

Album release gig in

Músaem an bPiarsach

St. Enda's Rathfarnham

15/10/16 ; 3:30pm

ART: 2016 is the Arts Council's programme as part of Ireland 2016. It is a diverse and distinctive public showcase of Irish art which will be presented across Ireland and abroad throughout the year. Key programme strands include the Open Call National Project Awards, which feature cutting-edge, contemporary art events in dance, visual arts, poetry and music; the Next Generation Bursary Awards which highlight the work of eighteen rising stars of Irish art; and A Nation's Voice, an open-air, free concert at Collins Barrack on Easter Sunday, featuring new choral and orchestral work by Shaun Davey and Paul Muldoon, and the voices of a 1,100-strong choir. The programme also includes a selection of national touring productions.

ART: 2016 is supported by the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht through its Ireland 2016 Centenary Programme and is created with a range of partners; local, national and international